Damien O’ Brien completed his MA on the Art History Cities course in September 2017, and here he discusses the subject of his well-received dissertation on the 20thc American painter Florine Stettheimer (1871-1944):

Damien O’ Brien completed his MA on the Art History Cities course in September 2017, and here he discusses the subject of his well-received dissertation on the 20thc American painter Florine Stettheimer (1871-1944):

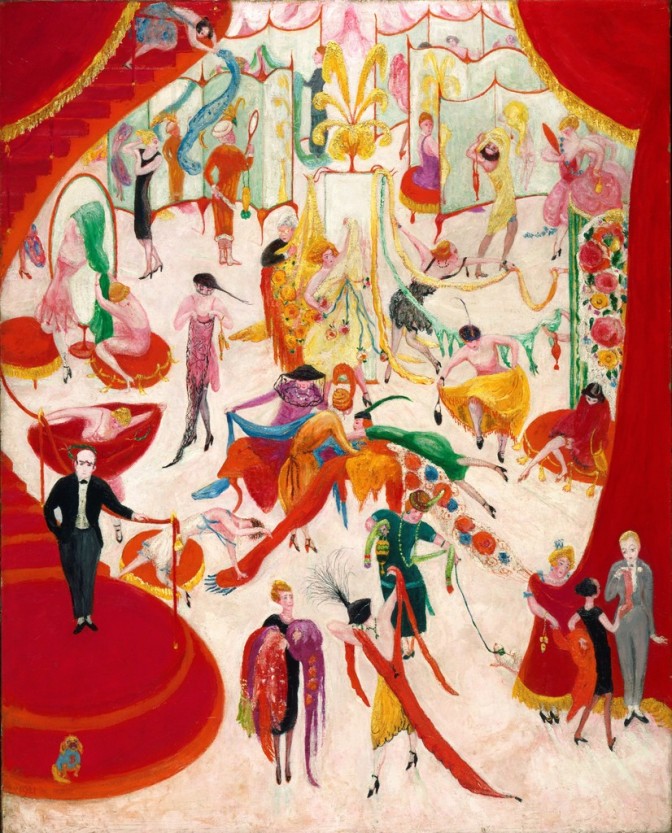

I went to see an exhibition of Stettheimer’s paintings in 1995 on the recommendation of a friend. It made quite an impression on me, and I had never seen anything quite like it. Her large canvases are theatrical: curtains frequently appear, behind which she places human figures in balletic movement. The Ballet Russes was to be a continuing source of inspiration for her. She took elements of this, and applied it to her canvases. What I found striking was a vitality in these compositions. Humour is an element in Stetthheimer’s oeuvre. In Spring Sale at Bendel’s (shopping is an unlikely subject in art) she elevated this mundane subject to a theatrical tour de force in a way that reminds me of a crowded Bruegel scene.

Florine Stettheimer, Spring Sale at Bendel’s, 1921, oil on canvas, 127 × 101.6 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

I had not read or heard anything about her since this encounter with her work, and when, in 2016, I decided to choose Stettheimer as the subject of my MA dissertation I went searching for information on her. I found there wasn’t much: only one monograph on her written by Barbara Bloemink, The Life and Art of Florine Stettheimer (Yale University Press, 1995; Stettheimer was also the subject of Bloemink’s PhD thesis), and a couple of exhibition catalogues. But there was no catalogue of her entire oeuvre to offer further help with my research. There were other challenges, such as the fact that Stettheimer’s paintings are scattered across America. In New York, the Metropolitan Museum, has four large canvases known as The Cathedrals Series (see below) on display in its Modern American Wing, while Columbia University is also an important repository of Stettheimer’s work and related material. So, a research trip to New York was necessary…or two, as it transpired.

The author (furthest from the camera) in front of Stettheimer’s Cathedrals Series at the Metropolitan Museum, New York, in December 2016.

My research took some organising. Before I arrived in New York, where is where most of my research would be conducted, I needed to make some contacts among the people who could give me access to relevant archives. There were many phone calls made and emails written, and one of my lecturers, Dr Roisin Kennedy, wrote letters of introduction for me, and this allowed me to arrange my schedule in advance. Over Christmas and New Year 2016/ 17 I spent three exhilarating weeks in New York looking at Stettheimer’s work and immersing myself in archives related to her. My first port of call was the Whitney Museum of American Art, and then a day each at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), and The Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was only when I arrived at Columbia University (see below) that I realized the vastness of its Stettheimer archive. But I had been granted a research pass for only a day.

The (lovely) Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York, January 2017.

They had countless boxes containing thousands of items on Stettheimer, and thankfully I obtained an extended research pass, granting me access for one week. I was able to look through Stettheimer’s early sketchbooks, and these recorded the range of her interests and her travels in Europe. I noticed her attempts at pointillist, symbolist, and other stylistic modes, and I could trace her progression in style and technique (Stettheimer had a traditional training in art at the Art Students League, New York, from 1892 to 1895). It was here that I felt I was getting a grasp on my subject, but, what to do with all of this information? I took hundreds of photographs of the sketchbooks, documents, and of the paintings themselves. My notebooks were filled with observations and ideas. One could continue looking, reading, and taking notes indefinitely. But there are deadlines, alas.

I wanted to understand where Stettheimer fitted in – where was she located in a broader art historical and cultural context? It would be helpful, I thought, to know what her contemporaries were doing in New York. While I was researching at MoMA (Stettheimer’s first retrospective was organised here in 1946 by her friend Marcel Duchamp) I went to see their Francis Picabia exhibition, and then I visited the Met. Breuer (The Metropolitan Museum’s offshoot for modern and contemporary art) to see the Marsden Hartley retrospective. Both artists appear in her group paintings (I also later took a trip to The Royal Academy, London, in June, to see its exhibition ‘America After the Fall: Paintings in the 1930s’). These diversions were not absolutely necessary, but I did find them helpful. There were other fun expeditions, such as walking, in freezing January temperatures, from Stettheimer’s grand apartment building, the Alwyn Court at 58th Street and Seventh Avenue, to the beautiful Beaux Arts Building at Bryant Park, where she had a studio.

(above left) Alwyn Court, midtown Seventh Avenue, where Stettheimer, her mother and sisters had an apartment; (above right) Beaux Arts artist studios (built 1901) at Bryant Park – Stettheimer had her studio here. Photographed in January 2017.

When Stettheimer returned to New York in 1914 after years of travelling in Europe, she wrote a poem about her observations of the city:

Then back to New York

And Skytowers had begun to grow

And front stoop houses started to go

And life became quite different

And it was as tho’ someone had planted seeds

And people sprouted like common weeds

And seemed unaware of accepted things

And out of it grew an amusing thing

Which I think is America having its fling

And what I should like is to paint this thing

(Stettheimer. ‘Crystal Flowers’)

New York is the subject of many Stettheimer paintings. ‘Cities’ was the programme title and theme of my M.A. course, so I kept that in mind while writing my dissertation. Her Cathedrals Series at the Met. are her secular shrines to New York City, and her paintings generally combine patriotism with irony, and the astute observations of the returning émigré. The American flag appears frequently. There are eagles, and a gold impasto George Washington in Cathedrals of Wall Street.

Florine Stettheimer, Cathedrals of Wall Street, 1939, oil on canvas, 152.4 × 127 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Cathedrals paintings always make me smile. Stettheimer’s horror vacui approach is startling when seen surrounded by her contemporaries’ sober, abstract canvases at The Met. Stettheimer’s most astute and humorous painting about contemporary art and art institutions in New York is Cathedrals of Art. This is her final painting. It remained unfinished at her death in 1944.

Florine Stettheimer, Cathedrals of Art, 1942-44, oil on canvas, 153 × 127.6 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

I decided to concentrate on the following themes related to Stettheimer: Americanness and Modernism; artistic influences, and humour. Her paintings are funny. Humour in art is sometimes viewed with suspicion, but funny is not necessarily the opposite of serious. I discovered that writing about humour is tricky. The New Yorker contributor, E.B. White (1899-1985) wrote, ‘Analysing humour is like dissecting a frog. Few people are interested and the frog dies of it’.

By chance I then read a small notice in the New York Times announcing a forthcoming exhibition, ‘Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry’ at the Jewish Museum, New York. A Stettheimer exhibition is such a rare event, and was so fortuitous to my research that I contacted the curator, Stephen Brown, who sent me an invitation to the opening on the 2nd of May. There were about fifty paintings and drawings, and models for opera and ballet. I returned several times. I loved this exhibition, and found it really helpful. The arrangement of so many of Stettheimer’s paintings in this setting helped to contextualise the work.

Although writing is a solitary endeavour, my research was facilitated by many good people who made the whole process pleasant. I was very fortunate to have Prof Kathleen James-Chakraborty as my supervisor. Her knowledge of American modernism is encyclopedic, and her insight, comments and suggestions were invaluable. I am grateful to the many people who opened their archives and welcomed me. The collaborative element of my master’s was vital to my work, and was the most rewarding part of it. I have remained in contact with archivists and curators in New York. Stephen Brown, who curated such a terrific exhibition, was particularly generous. He sent me all the press releases related to the retrospective. He also met me to discuss his exhibition and Stettheimer’s work generally . I have benefited from all their contributions, and have been surprised and heartened by their generosity.

My dissertation will, I suspect, languish for eternity in the depths of the Art History dungeon, with only the occasional nibble from a curious mouse. And that’s ok. I hope I have brought some insight to the work of a vital artist whose place at the vanguard of American modernism between the Wars is being reaffirmed. It was a privilege to be part of this dynamic course at the School of Art History & Cultural Policy, UCD.

Good luck to the current M.A. students. Writing is hard! At times it feels like it will never come together. But it does, and it’s worth it.

Cheers!

Damien.

April 2018

You can read Damien’s Venice travel diary here:

https://ucdarthistoryma.wordpress.com/2016/04/

Applications for the UCD Art History MA for 2018/ 19 are now being invited – click on the following links for further details:

https://sisweb.ucd.ie/usis/!W_HU_MENU.P_PUBLISH?p_tag=PROG&MAJR=Z344